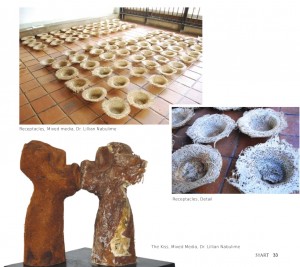

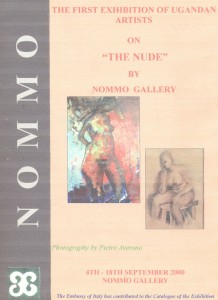

On 4 September the Nommo Gallery launched Nude 2000 amid high expectations, pomp and ceremony[i]. Its subject matter was not like an exhibition that was held at the newly opened Cassava Republic[ii] in which Akiiki and Etyang featured artworks celebrating Uganda’s traditions, traditional dresses and dress codes. It was also distant from Bruno Sserunkuuma’s ceramics show at the French Embassy in which the artist attended to the mastery of skill[iii].

By Angelo Kakande F.J 2012

This is Part II of the essay, click here to read Part I first.

The Director of Nommo Gallery, Emanuel Mutungi, wrote in the catalogue explaining the objective of the show. He argued that Nude 2000 was intended to demystify the human body which had been “abused by many” religious and other negative stereotypes. He wondered why “[n]obody hates himself or herself yet many of us shy away when we look at our [naked] bodies” (Mutungi 2000, n.p). These views were reproduced in the press; they were published in The New Vision of 1 September 2000 for example. Mutungi does not answer his question.

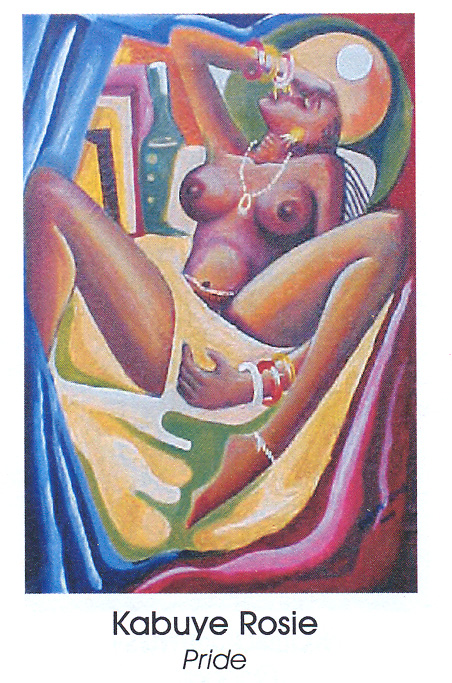

![Cover of the catalogue The Nude 2000 Exhibition]()

Cover of the catalogue The Nude 2000 Exhibition

However in my estimation Kyeyune (2000, n.p) provides some good answers to it. He wrote in the catalogue that Nude 2000 served two functions; it allowed art to function “as a piece of reflection as well as aesthetic appeal” (Kyeyune 2000, n.p). He, without elaboration, observed that Nude 2000 captured the “spirit of its time”. He thus persuaded those who visited the show to view “nudity in context”. He was concerned that the exhibition risked “standing ambiguously except when interpreted in its [social political] context.”

Clearly Kyeyune was alluding to the context in which, as Trowell (1954) observed, contemporary art in Uganda mirrors its society as it assumes a political function—for instance the political nexus in Kakande (2008) and the gender imag[in]ed in Tumusiime (2012). He observed that the context in which Nude 2000 was located was one in which the mass-circulated image of a naked person was one of embarrassment.

The press was awash with pictures of unclothed and half-clothed, accompanying stories concerning adultery, rape, murder, theft, etc. Let me agree with him and mention that faced with a rising criminality, mob justice became a convenient way of dealing with crime; it still is[iv]. Most crucially, at the time of Nude 2000 graphic images of half-clothed and totally unclothed people, some badly beaten or set ablaze, were common in the vernacular and English language press[v]. So Kyeyune’s argument is valid.

Nude 2000: A Strategy for Free Speech and Artistic Expression

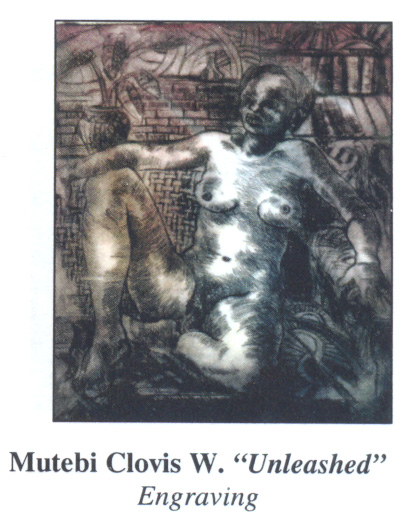

I concede that Nude 2000 was marked with variety. Some artists experimented with material and media: Byuma explored ebony wood in sculpture and did Nudeness; Kabiito Richard presented a collage resulting from a combination of traditional baskets, basketry and oil painting; Mzili Mujunga did a wood print in his Silhouette; Ernest Kigozi exhibited Two men, a watercolour in which two nude male figures are set in a ritual dance or wrestle; Lydia Mugambi presented Nude, an experimental project in which she used black ink on paper; Margaret Nagawa used water colour and chalk on paper.

Some works were a product of creative imagination: Joseph Sematimba’s Nude depicting a head-less female figure reclining across the picture space is a good example. Others were done from a life class: Stephen Gwotcho’s Seated Lady can be cited.

Many of the works were about nudity as art. It is therefore my opinion that these works had nothing to do with embarrassment. There was nothing sexually explicit about them.

![]()

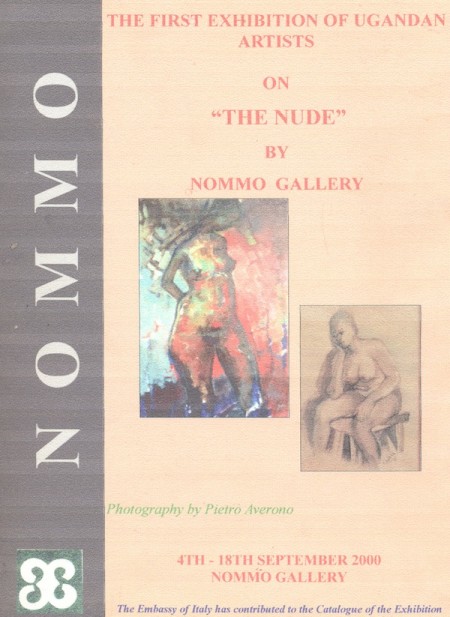

I also admit that some artists did work which was graphic bordering on vulgarity. For example Fred Kizito Ec[s]tasy was probably the most sexually explicit. The artist depicted a naked couple. To the right the woman faces up and folds her hands backwards while setting her legs apart to allow the man to stand between them. The man holds his erect penis in his right hand as he advances towards the woman. The painting seems to have been cropped out of an X-rated movie, its modernist style ensures its position as art.

![Fred Kigozi ECTASY]()

Fred Kigozi ECTASY

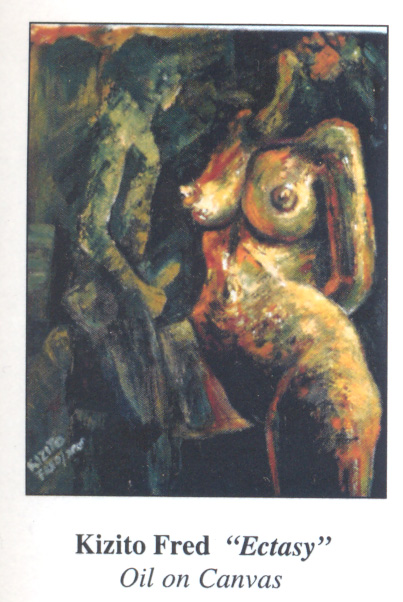

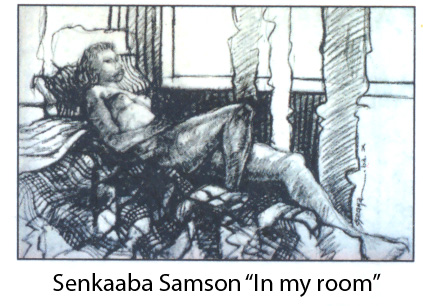

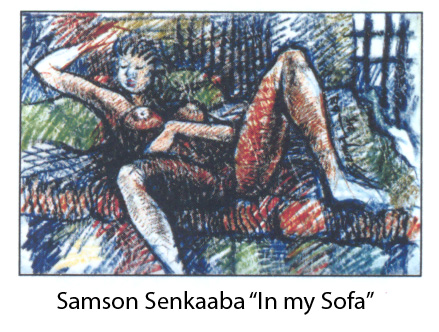

But some images were subtly erotic. For example in his Unleashed, Clovis Mutebi captured a reclining female figure. Unlike the reclining figure in Samson Ssenkaaba’s drawing titled In my Room, in which the woman comfortably claimed her private space and controlled it before using it to explore the erotic possibilities of her body, it is as seen in the artist’s other painting titled In the Sofa, Mutebi’s figure sits in an uncomfortable pose set in a disorganised space. She is disorientated. She supports herself (or leans) against an assortment of objects which litter her space.

![Clovis Mutebi UNLEASHED]()

Clovis Mutebi UNLEASHED

![Samson Ssenkaaba IN MY ROOM]()

Samson Ssenkaaba IN MY ROOM

![Samson Ssenkaaba IN MY SOFA]()

Samson Ssenkaaba IN MY SOFA

By the two artists appropriating the gesture of a woman spreading her legs (which is taboo in most communities in Uganda) they begin to use nudity to question the character of women and women spaces—a critique which is also seen in Johnson Mwase’s Untitled.

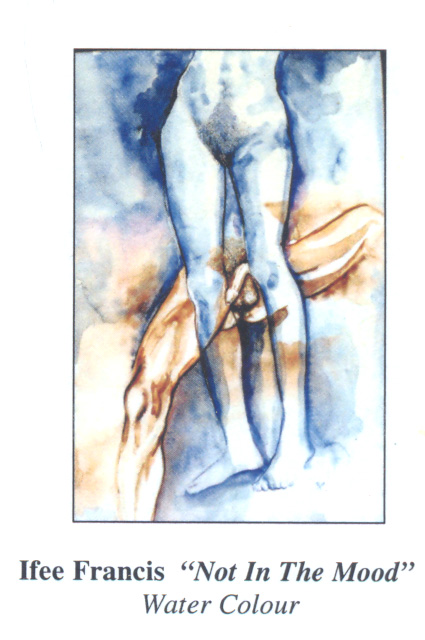

Other works were ambiguous but communicated an urgent message. For instance Francis Ifee painted Not in the mood. He depicted an identifiably heterosexual couple. The woman stands in front, she shifts her right hip allowing her left leg to loosen and part creating a space through which we see a flaccid penis of the man seated at the back. The couple is anonymous thus not embarrassed. The artist attends to male and female anatomy as if to invite the beholder to compare and contrast the two. Yet he explained to Daily Monitor published on 7 September 2000 that his images were part of the struggle to control the spread of HIV-AIDS[vi].

![Francis Ifee NOT IN THE MOOD]()

Francis Ifee NOT IN THE MOOD

HIV/AIDS stands for the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, a disease which weakens the body by attacking its defence mechanism. By 2000, the HIV/AIDS disease had become a scourge inviting pragmatic solutions. Promiscuity and unsafe sex were blamed for spreading the disease. In such an environment the state responded by rounding up all alleged prostitutes and detained them under inhuman and degrading circumstances[vii] and charged them with trumped up charges of being idle and disorderly. It still does today[viii].

This intervention was welcomed by the conservatives and traditionalists. However, it was gendered and intended to punish women and not men[ix]. It attracted negative criticism including from within the ruling party[x].

Unsightly Nudes to Communicate Social Messages

The body politic had its own interventions, including those which bordered on criminality. To demonstrate, on 16 September 2000 The New Vision published a story in which 45 year-old Marita Aketo “had sex with her son Elemu Juventine (25) as a way of protecting him from acquiring Aids”. This act is illegal since the combined effect of Sections 149 and 150 of the Penal Code (Cap. 120) criminalises incest. The incident shocked Aketo’s neighbourhood; she was rejected as insane. However, Aketo explained that “it was safer for him [meaning her son] to satisfy his sexual needs with her instead of going out for girls” and risk his life.

It is my contention that in light of interventions like Aketo’s, Ifee’s works gain new meaning. The artist used unsightly nude images to communicate a socially-relevant message although it was ambiguously expressed.

In summary, on 19 September 2000 Daily Monitor published an article titled “You Don’t say! You Don’t Say!”[xi] Coming a day after the closure of Nude 2000, the article evaluated the success of the show. “How do you undress a strange woman, put her against a wall and get away with it?” the author asked. “You paint her” he responded suggesting that the show had demystified the human body.

This view was probably informed by the largely rehearsed script circulated by Mutungi, the Director of Nommo Gallery, and published in several articles[xii]. It harks back to those romanticist notions in which artists (and art) led public opinion.

As I have argued elsewhere public opinion and policy in Uganda is not shaped by exhibitions of art (see Kakande 2008, 326). But since what we read in Daily Monitor was the stated objective behind the Nude 2000, I would argue that the show was a therefore a success to that extent.

Nevertheless, I am not prepared to admit that the show completely changed attitudes towards nudity. For the avoidance of doubt, nudity is still taboo in spite of the fact that it is freely circulated in art and art exhibitions.

What Nude 2000 succeeded in doing, in my opinion, was to open another public forum for a discussion on the sensitive subject of the naked body. In the process artistic expression became a vehicle for free speech allowing the production, transmission and possession of unsightly visual information, some of which was sexually explicit. This right is guaranteed under domestic, regional and international law.

Clearly then Nude 2000 must be remembered for having unfolded a pack of strategies through which artists can enjoy it.

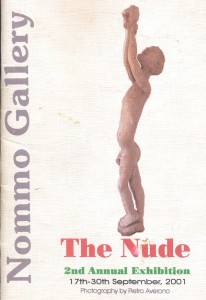

Nude 2001: Female Erotica as Expression

On 17-30 September 2001 Director Mutungi fulfilled his promise on hosting a nude exhibition every year at the Nommo Gallery. 115 artists participated (presenting 185 works). Clearly then, compared to Nude 2000 which attracted 38 artists (presenting 88 works), it is arguable that the success of Nude 2000 sparked off an interest in the production and exhibition of nudity—and this point was made in an article published in Daily Monitor published on 15 September 2001[xiii]

Edris Kisambira wrote a review in The New Vision, in which he characterised works which captured the female nude as alluring, adding that Nude 2012 had some of some of the most graphic expressions of the nude female forms to be ever displayed in Uganda[xiv].

Kisambira further explained why Nude 2001 attracted more artists and artworks. This was because the works exhibited in Nude 2000 were “scooped off the wall so fast”. In other words, and this is how Mutungi was quoted to have seen it, there was lot of “public interest in the subject” of nudity.

Let me point out that the exhibition had more female subjects. It had nude men and children as well. Let me also observe that the message in some of the works was ambiguously expressed.

For instance Benedict Bukenya’s Ripening series and his Stretching lacked clarity. Some works with female nude were not graphic at all. For instance Ibrahim Kamya’s sculptures Untitled and Happy Nude, Norman Koko’s sculpture Maliced, as well as Francis Luyinda’s Suckle on the Move and Lutwama Romano Jr’s Beauty in Nudeness, Kyazze Muwonge’s glass works titled Sublime, Charles Kamya’s Nude, Paul Kitimbo’s Nude, Paul Bazibu’s Blue Love and Ceasar Baba’s Nude Woman.

Other artists stayed away from the controversial subject of the genitals as if to preserve the integrity of the subject. Joshua Agaba’s’s painting Look at Me, Rhami Balyeku’s My Back, Paul Bazibu’s The Butt can be cited as examples. Although based on a nude, these works were not graphic at all. The artists explored material and attended to form, volume and balance, understanding of design, control of the media, colour, picture space, composition, balance and the golden section.

![]()

Mutungi explained that like Nude 2000, Nude 2001 was educative. It helped the public “to learn more about the anatomy, the beauty of the body and free the mind from unnecessary misconceptions and to upraise the level of art appreciation in Uganda”.

In line with this stated objective in his painting, titled Comparison, Leopold Higiro presented a soft and feminine female figure juxtaposed against a rough and muscled male figure. The two are set in tableaux to allow the audience to draw the distinction between male and female bodies.

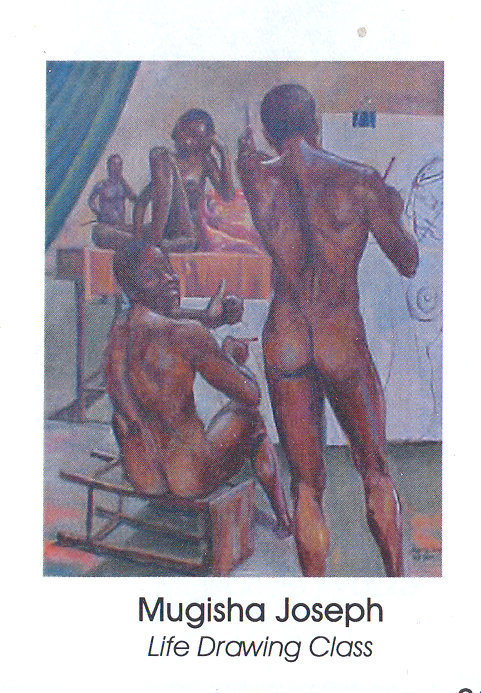

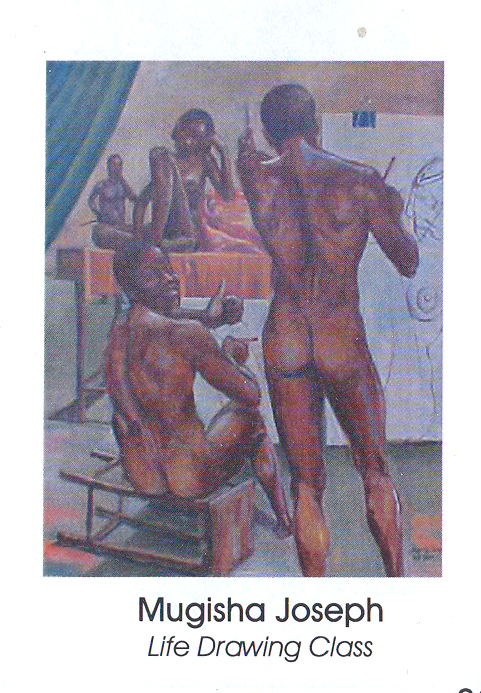

Joseph Mugisha described what happens in a life class: Human beings pose nude. However to show that there is nothing awkward and taboo about it, in his Life Drawing Class he painted nude male students drawing from a nude female model. Wearing a smile, one of the students turns to the beholder and makes a thumbs-up gesture. Mugisha thus demystified the production of nude art while bringing humour into the discussion on the visualisation of nudity. The same can be said of Francis Sseruwu’s Who Cares.

![Joseph Mugisha LIFE DRAWING CLASS]()

Joseph Mugisha LIFE DRAWING CLASS

Nonetheless there was lot of energy and varied responses seen in the works displayed on the show. This confirmed that the pre-set objective was not restrictive. Artists used it only as a point of departure. They explored and experimented with varied materials (wood, metal, banana fibres, clay, oil, glass, coloured pencil, crayon, charcoal, wash, etc), techniques and styles to unlock their creative potential and artistic expression.

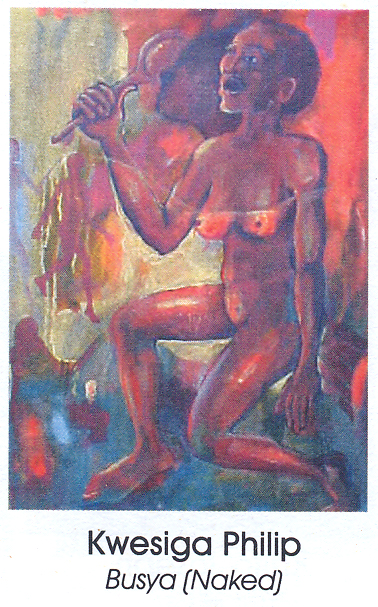

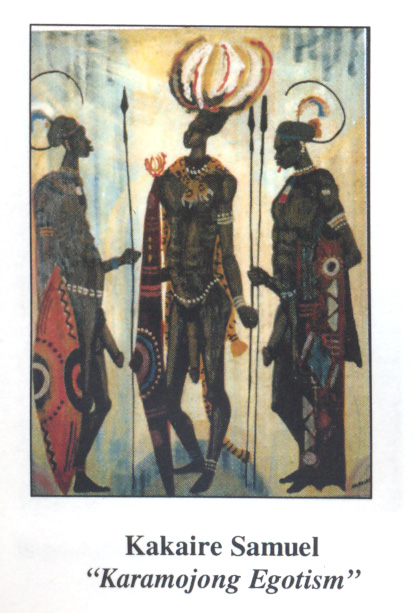

Some even used it as an occasion to celebrate issues of African identity and Uganda’s culture: For instance Yoshi Ishida volarised the identity of the Baganda (a dominant group in Central Uganda) in his Buganda Woman. Jude Kiwekete Kateete in his African Beauty Queen, and Joseph Kizito in his African Treasure, celebrated the identity of an African woman. Rashid Mpenja drew on the decorations, and decorativeness of traditional bead work called endege, to create his Endege series.

![]()

Sexuality and eroticism

Now, inaugurated on 16 July 2001 The Red Pepper, in the words of Major General Salim Saleh (President Museveni’s brother), was to publish stories based on controversial subjects: HIV-AIDS, exploitation, etc.[xv] These stories were spiced, or even hyped, by cartoons in which heterosexual couples had sex. Their spaces are identifiably private. For instance the couple in its edition of 18-24 July 2001 The Red Pepper published a cartoon of a couple having sex on a couch under the cover of a blanket.

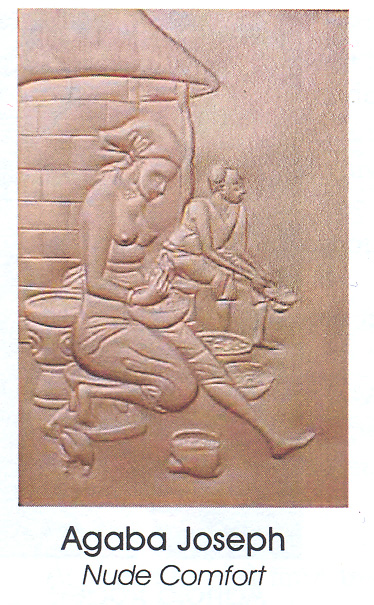

This link between sex, sexuality, eroticism and the private (and individual) space was clothed with a modicum of decency. This position was taken in the Nude 2001. The women in Joseph Agaba’s Nude Comfort, Rogers Adhola’s Attitude, and Silvester Kibiyira’s Beautiful Enough came from different social classes. They attend to sexuality and eroticism. They however had a significant amount of cloth wrapped around them to ensure that they are socially appropriate.

![Joseph Agaba NUDE CONFORT]()

Joseph Agaba NUDE COMFORT

![Sylvester Kibiyira BEAUTIFUL ENOUGH]()

Silvester Kibiyira BEAUTIFUL ENOUGH

I submit that this is generally an expected from patriarchal societies like Uganda. As they stroked controversy some artists have joined The Red Pepper in the propagation of cultural expectations about sex, sexuality and the human body.

The Red Pepper also circulated pictures of international women celebrities cropped from the internet or the discreetly circulated pornographic magazines. This was possible “Pornography [sold] Big” as it was observed in the Sunday Vision published 30 September 2001; the very a day when Nude 2001 ended. It captured Toni Braxton and Britney Spears in erotic and seductive poses. The mainstream press also sometimes published such images in full colour. To give an example, on 16 September 2001 Daily Monitor published describing her as the hottest pinup in schools[xvi].

This came two days after 14 September 2001 when The New Vision published a photo of Victoria Beckham, singer and wife of football star David Beckham. With her body facing the back she turns her head to face the reader, causing her hair to swirl as she reveals her much celebrated identity, as one of the spice girls, and flair[xvii]. She was described as a “role model” confirming the role of the print and electronic media in forging a ‘global culture’ centred on celebrities-as-role-models. In response phenomena like ‘skin-breaching’, ‘hair extensions’, etc., have become popular among women. Many have health implications. However local industries, like Samona Industries among others, have been established to cater for the growing local market for them. They are sources of revenue and employment.

I contend that the many of the works seen in Nude 2001 had been informed by the celebrities circulated by the internet and print media. They have attributes of fair skin, slender bodies and long hair suggesting that they were not done from any life class or private drawing session.

In fact in our interview with Amanda Tumusiime she confirmed to me that her student James Sonko developed his Nude from a pornography magazine which he also carried to the drawing class[xviii]. This can be verified. In his Nude Sonko depicted a young, supple woman dominating a space. She kneels on a loosely folded fabric allowing her athletic upper body to fall backwards and her sharp breasts to thrust outwards. In a display of flair and style, she holds her thick, long, dark hair as she seductively winks and smile to the beholder. The painting is bathed in a luminous red and yellow colour palette which adds to its vibrancy and vitality. This painting, and two other works exhibited by Sonko, was far removed from the drawings he did out of imagination and the drawing class.

![James Ssonko NUDE]()

James Ssonko NUDE

Mass-circulation through Red Pepper

The Red Pepper also publicised a new type of dance in which seductive dancers performed in drinking pubs like Will’s Café at Kabalagala, Kiman* zone at Kalerwe (read Kimana “named after the female genitalia”[xix]), Sax Pub on Luwum Street. Groups like the Shadow Angels, the Amarulas, the Queen Dancers Family Group actively performed and promoted this dance called kimansulo. With minimum training girls where guided and encouraged to dance and strip naked allowing their male audience to touch their genitalia, take pictures of it and have sex with them on the stage in front of an audience.

The New Vision reported that taking pictures of the female genitalia became brisk business in suburbs like Kawala Zone, Jambula and Kimombasa[xx]. At Kimombasa, in Bwaise, such sex performances would attract crowds as couples outcompeted each other in what was called “sex competitions”[xxi]. By August The Red Pepper was regularly publishing photographs of couples having sex in all sorts of public places[xxii].

There is an interesting discussion in which Tumsiime (2012, 221-227) has argued that the print media and kimansulo dymstified the naked female body and gave it a public face. It is my opinion that artists contributed to this public face through Nude 2001. The exhibition took nakedness and erotic imagery to the centre of haute couture and mainly high art as it fused the line between high art, low art, public culture and public opinion.

The Red Pepper also mass-circulated sexually explicit images. For example on 8 August 2001 it published a photo of a couple having sex at the veranda of a run-down “pit latrine behind a church”. I admit that this image was sexually explicit and probably offensive if children saw it. Critiques attacked it and related images.

I however strongly argue that critiques must move beyond form to establish the content and context of the material visualised.

In my opinion, The Red Pepper used explicit imagery to raise serious governance, moral and economic issues. This was based on tabloid’s professed belief that “[i]t is exposure that fights evil.” “What a shame!” was the headline accompanying a picture in which a drunken man fondled the genitalia of an equally drunken woman at Sax Pub located at Luwum Street. Using this, and related pictures, the tabloid criticised the deterioration in morals in most parts of Kampala “night clubs and those involved has no regard for other members of the public”[xxiii]. Through what it called “medical briefing” the tabloid advised young people on how to avoid sexually transmitted diseases[xxiv], juvenile sex, drug abuse and other modes of irresponsible behaviour.

This, in my humble estimation, was the message behind the front-page coverage of an incident in which students were taken, for a retreat, to a beach at Entebbe road. While there, students turned to alcoholism, premarital sex and drug abuse. The Red Pepper used the occasion to warn parents against sending their children to end year school parties in the course of which they engaged into immorality and bad behaviour because of lack of supervision and guidance. The article was accompanied graphic images of three juvenile couples having sex.

Unfortunately this context was often missed (it still is). Critiques have attacked it[xxv] suggesting that the sole target of The Red Pepper is profit maximisation. In the words of Pastor Martin Ssempa, The Red Pepper “is just battling to make money…they are simply exploiting the public”[xxvi]. In 2001 one reader harshly criticised and blamed The Red Pepper for having created a forum in which “exposing underwear, nude bodies and obscene actions are unfortunately becoming rampant in the country”[xxvii]. Traditionalists and radical conservatives have called on government to ban the publication.

As a result in October 2001 the Police raided, searched and jailed Richard Tumusiime, the Editor of The Red Pepper[xxviii]. This was part of a well-publicised crackdown, intended to appease the moralists and conservatives, in which so-called prostitutes (or sex-workers) were randomly, arbitrarily and inhumanely arrested, loaded on to trucks and detained[xxix] in defence of morals.

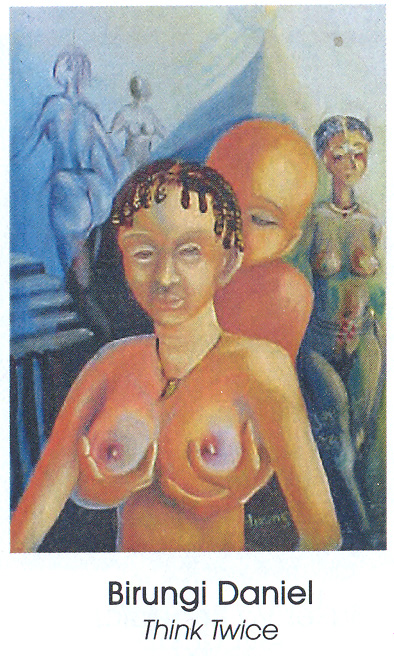

I suspect that Nude 2001 was permeated by this debate. Daniel Birungi did his painting titled Think Twice. He depicted a nude female figure standing in the foreground. She spreads her hands outwards allowing another figure to fondle its breasts. To confirm that the woman before us is not following traditional conventions, she wears a sophisticated coiffure and jewellery.

![Daniel Birungi THINK TWICE]()

Daniel Birungi THINK TWICE

The artist seems to advise against some illicit and casual sexual intercourse. As such he introduced other equally nude and non-traditional women into an otherwise calm and (probably) private space. They casually roam around the space in manner which suggest that they are on the loose in such of sexual partners just like the strollers in Sylvia Katende’s On the Streets.

![Sylvia Katende ON THE STREETS]()

Sylvia Katende ON THE STREETS

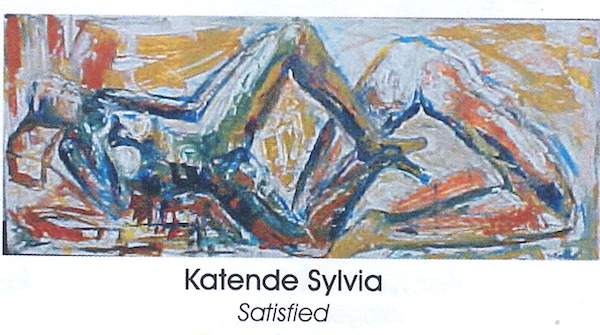

Very interestingly Katende seems to suggest in her Satisfied (which, by the way, was also exhibited during Nude 2001) that the women before us have an insatiable libido.

![Sylvia Katende SATISFIED]()

Sylvia Katende SATISFIED

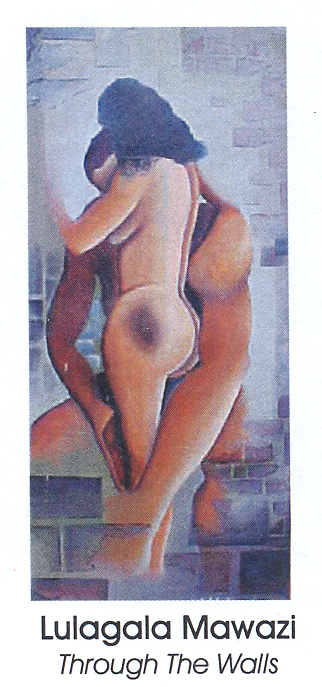

Where they find no man they lie down and spread their legs open while indulging in all forms of autoerotic behaviour. This is how they, probably, can get satisfied. These paintings, just like Lulagala Mawazi’s Through the Walls, were in many ways erotic.

![Mawazi Lulagala THROUGH THE WALLS]()

Mawazi Lulagala THROUGH THE WALLS

Intriguingly the artists were not arrested. Although it was hosted just behind the residence of the President of Uganda, the exhibition was not disrupted.

Innocent and inaccessible

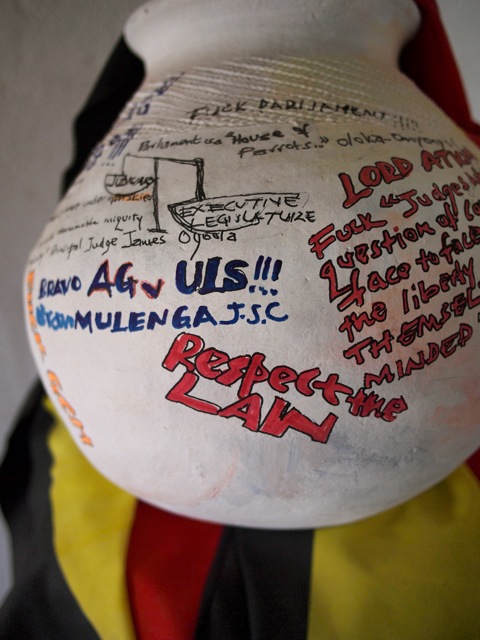

This then raises three issues: Firstly, Nude 2001 was seen as a form of artistic expression whose sanctity, as I earlier mentioned, is protected under the Municipal law, the Common law and International law. This is the context in which Ssekisonge argued in Daily Monitor published on 28 September 2001 that “nude must not be offensive…it is about innocence….”[xxx]

Evelyn Kiapi Matsamura encouraged Ugandans to visit the show. There was “no reason to shun the exhibition” she explained. As such the artists and organisers could not have been properly charged under Section 166 of the Penal Code Cap. 120 or indeed any other law.

Indeed Daily Monitor published photographs of works exhibited at the Nommo Gallery. However it could not have been charged under Section 7 of the Electronic Media Act Cap. 104, Section 3 of the Press and Journalist Act Cap. 105 or indeed under the an other Municipal law, the Common Law or International law.

Secondly, the exhibition was not accessible to the masses. It attracted the elite middle class and tourists. In fact a photo published in Daily Monitor of 20 September 2001 captured two men, one wearing a necktie (an attribute of the middle class) inspecting Lwasampijja’s Mystery Woman[xxxi]. In this sculpture the artist represented a blindfolded woman tracing her way through a space. That she is wearing high-heeled shoes confirms her access to non-traditional dress codes. It further confirms that she is an urban woman.

Thirdly, couched in modernist vocabularies of pictorial anatomy and visual vocabulary, Nude 2001 remained inaccessible to the majority of Ugandans who are visually illiterate and can only access the literal meaning available in the photos published in The Red Pepper among others.

Seen in this light one can safely conclude that the exhibition was not a threat to the State and public morals generally. On the contrary it may have been seen to be resolving a more socially relevant.

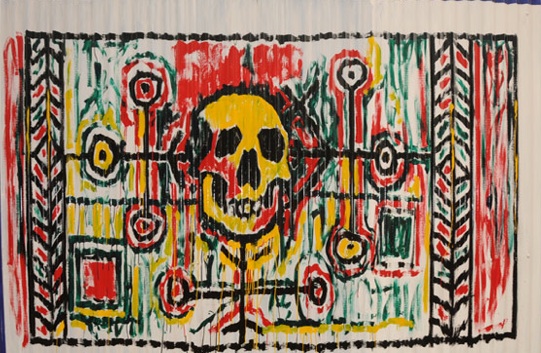

This strategy of using erotic (but generally female nude) imagery to fight vice can be traced back to the 1980s when Musangogwantamu did his sleep series. For example in Sleep v (1987) Musangogwantamu depicted a woman. She rests against a pillow closing her eyes while holding her breasts and directing her right hand, and the beholder in the process, to her legs which are spread to expose her white panties and allow her to caress her inner thighs. Musangogwantamu’s reference to the autoeroticism of the woman in this work was subtle (Tumusiime 2012) in order to preserve a decorum of modesty. However the work tapped into a wider criticism on the morals of urban non-traditional women. This criticism shaped the songs, theatre and film of the late-eighties; Musango escalated it in his Emptiness of lust (1987).

![Musangogwantamu EMPTINESS OF LUST]()

Musangogwantamu EMPTINESS OF LUST

In Emptiness of lust we see a woman filling the entire picture plane. She closes her eyes and throws her head backwards causing her hair to swirl as she gasps for air. Her body is ruptured by her preoccupation with material things which ooze from her now decomposed body.

In [t]his work the artist presents a moral critique highlighting the folly of overindulgence with the material things (jewellery, shoes, among other things symbolised by improvised objects) and worldly excesses. That this criticism was directed towards women has been rejected as a visualization of the misogyny; the fear of Uganda’s women who, since 1986, have broken chains imposed by tradition and taken up new positions in Uganda’s social, economic and political spheres (cf Tumusiime 2012:163).

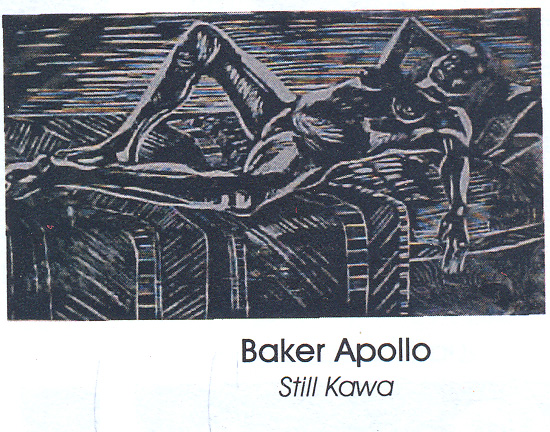

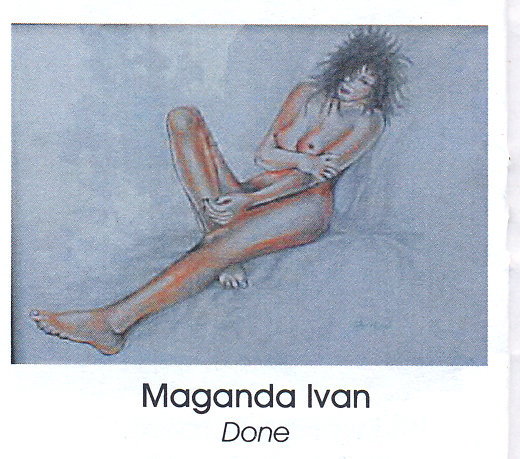

In Nude 2001 Apollo Baker did his Still Kawa and For How Long whose gesture, figuration and composition hack back to Musangogwantamu’s Sleep series. Ivan Maganda’s Done and John Matovu’s The Nude Woman point to autoerotic behaviour of middleclass elite (but mainly urban) women seen in Musangogwantamu’s sleep series (Tumusiime 2012).

![Apollo Baker STILL KAWA]()

Apollo Baker STILL KAWA

![Apollo Baker FOR HOW LONG]()

Apollo Baker FOR HOW LONG

![Ivan Maganda DONE]()

Ivan Maganda DONE

In many of the works the artists used nudity to expose the materialised woman subject who has subverted conventions, traditions and traditional mores. In a patriarchal country struggling to control the woman in the public space, this message was relevant and welcome. This may explain why the artists and the show were not touched.

Exploring the Nude for Art

In summing up, Nude 2001 grew from the success of Nude 2000; the two shows had a common agenda of mystifying the naked body.

I however submit that that is not what is should be remembered for. In my opinion, it should be remembered for providing an occasion of the artists to explore the nude for art and for purposes of contributing to socio-political discussions in the country.

There were few male and child nudes on the show. The majority of artists captured a feminine, young “sharp-breasted”, sexually appealing female nude. This was at a time when serious doubt was being cast on whether “young ‘sharp-breasted’ women [were] still worth the time and money”.

By raising and answering this question Samuel Nsubuga wrote an article in Daily Monitor which was published on 30 September 2001 the day Nude 2001 ended. He submitted that young, sharp-breasted women are not worth the time and money. It was universally accepted that they come with a baggage without bringing added value in terms of sexual satisfaction. In fact it was older women who are better in bed because the sexual performance of a woman improves with age. He however argued that older men still needed ‘sharp-breasted’ women not for sex but to massage their ego and for public opinion.

It is thus my opinion and argument that the circulation of the nude, and mainly the female nude, in Nude 2001, had no sexual intentions however erotic some of the works may have been. Rather, it was for artistic, social and political expression. This is the legacy left behind by Nude 2000 it is the legacy passed on to Nudes 2012 which I attended to in the next section.

The third and final part of this Essay will be published in the January-issue of Startjournal.org.

Download the full essay as PDF (1,2 MB)

Angelo Kakande has researched extensively on contemporary Ugandan art and the connection to politics. He is currently the Head of the Department of Design at MTSIFA.

Endnotes:

[i] It was reported in The New Vision that Nommo Gallery was packed to capacity, guests “stretched their necks” in order to see the works. Over 100 works were exhibited. See The New Vision of 8 September 2000. Vol. 15, No. 214 at p.30.

[ii] For example there was a painting called “Lady in Busuuti”. Busuutii is a traditional garb won by women in Uganda. See Beauchamp Paula, “Cassava Republic Opens up” in The New Vision of 1 September 2000. Vol. 15, No. 208 at p.26.

[iii] This point was made in an article published by Juliet Nsiima and William Craddock in The New Vision of 15 September 2000. Vol. 15, No. 220 at p.30.

[v] For example Daily Monitor published a picture on 3 September 2000 of a half-clothed 49 year-old woman Margaret Apo. She had been “seriously beaten” for stealing a chicken. A similar punishment is seen a photo published by Daily Monitor of 8 September 2000. It this picture, Hudson Apunyo captured the back of a one Boniface Atime to show the grievous bodily harm inflicted on him by a mob through what the author called “a trend today of punishing thieves”. There was also a picture of abused children with badly wounded bodies. Now, these children, like Apo and Atime, should have considered themselves lucky; they escaped with serious injuries. The New Vision published on 20 September 2000 carried a “suspect bicycle thief” burning to death having been tied and set ablaze by an angry mob. See Sunday Monitor of 4 September 2000, No. 248 at p.15; Daily Monitor of 9 September 2000, No. 253 at p.17 and Daily Monitor of 19 September 2000 No. 262 at p.25; Mugenzi Joan, “Mob Justice, a Child of an Impotent Law” in The New Vision of 20 September 2000, Vol. 15 No. 224 at p.22.

[vi] Identified as serving a benevolent social duty two of his images were among the few reproduced in the press. They were accompanied with a caption that Was it Safe “had dark allusions to Aids and unsafe sex”. See Kimbowa Enock, “ ‘The Nude’ Show Opens at Nommo Gallery” in Monitor, of 7 September 2000. No. 251 at p.17.

[vii] To make this point Mr. Ras, a cartoonist in The New Vision , made a comic strip in which hordes of women had been piled at the back of a pick-up with their legs left turned upwards. See The New Vision published on 21 September 2000, Vol. 15, No. 225 at p.10.

[ix] Feminists and activist made this argument in the press. See Kyomuhendo Muhanga “Sex on the Street, What about the Buyers” in The New Vision of 21 September 2000, Vol. 15, No. 225 at p.11. Also see Chibita wa Duallo, “We Need a New Law against Prostitution” in The New Vision of 21 September 2000, Vol. 15, No. 225 at p.29.

[x] John Naggenda is the has served the ruling party since the 1980s. In his “One Man’s Weak” Naggenda criticized the criminalization of prostitution. He called for its legalization. See The New Vision of 30 September 2000. Vol. 15, No. 233 at p.10.

[xi] See A.R.K., “You Don’t say! You Don’t Say!” in Monitor of 19 September 2000. No. 263 at p.18.

[xii] Se for example Opolot Charles, “Artists Launch Nude Body Show” in The New Vision of 1 September 2000. Vol. 15, No. 2008 at p.26.

[xiii] See “Nude Exhibition starts Monday” in Daily Monitor of 15 September 2001 at p.18.

[xiv] See Kisambira Edris, “Alluring: Some of the most Graphic Expressions of Nude Female Forms to be Displayed” in The New Vision of 14 September 2001 at p. 28.

[xv] See The Red Pepper of 19-25 June 2001. Vol.1, No.1, at p.3.

[xvi] See “Popstar Madonna still has Her Lustre” in Daily Monitor of 16 September 2001 at p.19.

[xvii] See “Victoria Becham (Posh Spice)” in The New Vision of 14 September 2001 at p.28.

[xviii] Tumusiime Amanda, Interview with the author, 13 September 2012, at Makerere University.

[xix] See The Red Pepper of 18-24 July 2001. Vol.1, No.1

[xx] See Ocen Paul, “Kawempe Police Swear to Catch Bold Sex Workers” in The New Vision of 14 September 2001 at p.33.

[xxi] See The Red Pepper of 25-31 July 2001. Vol.1, No.5, at p.16

[xxii] See The Red Pepper of 9-15 August 2001. Vol.1, No.8.

[xxiii] See The Red Pepper of 25-31 July 2001. Vol. 1, No.5 at p.1

[xxiv] For example see The Red Pepper of 30 August – 5 September 2001. Vol.1, No.11, at p.17.

[xxv] In a letter to the editor a one Byamukam A from Bushyenyi advised The Red Pepper to keep outrageous images from the public view. “…keep them to yourselves”, he asserted.

[xxvi] See “Sempa, The Red Pepper Editor, Trade Fire over Porn”, in Sunday Vision, of 30 September 2001.

[xxvii] See The Red Pepper of 1-7 August 2001. Vol.1, No.7

[xxviii] See “Raided, Searched, Jailed, Bailed” in The Red Pepper of4-10 October 2001. Vol.1, No.16, p.1.

[xxix] See for example the photo in The New Vision of 16 September 2001 at p.7.

[xxx] See Daily Monitor of 28 September 2001 at p.9.

[xxxi] See Bruno Birakwate’s photo published in Daily Monitor of 20 September 2001 at p.8.